- Home

- Maike Wetzel

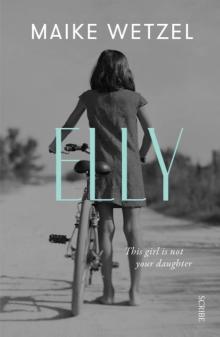

Elly

Elly Read online

Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright Page

Prologue

Queen

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Below Zero

10

11

12

13

14

Elly

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Elly

Maike Wetzel was born in 1974 and works as a writer and screenwriter in Berlin. She studied at the Munich Film School and in the UK. The manuscript of her first novel, Elly, won the Robert Gernhardt Prize and the Martha Saalfeld Prize. Maike’s short stories have been translated into numerous languages and received multiple awards. Her collection Long Days was published by Comma Press in 2008, translated by Lyn Marven.

Lyn Marven is a translator from German specialising in contemporary literature, women’s writing, and short stories. Her previous translations include Maike Wetzel, Long Days (Comma Press, 2008), Berlin Tales (OUP, 2009), and Larissa Boehning, Swallow Summer (Comma Press, 2016). Lyn is Senior Lecturer in German at the University of Liverpool, researching contemporary literature in German, with a particular interest in Berlin literature.

Scribe Publications

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

18–20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 USA

First published in English by Scribe in 2020

Originally published in German in 2018 by Schöffling & Co. Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH

Text copyright © Maike Wetzel 2018

Translation copyright © Lyn Marven 2020

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted.

9781912854127 (UK edition)

9781950354191 (US edition)

9781925849165 (Australian edition)

9781925938197 (ebook)

Catalogue records for this book are available from the National Library of Australia and the British Library.

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com

scribepublications.com.au

This story is not my story. I’m not sure which one of us it belongs to. It’s lying there in the street, it’s sleeping in our house, and yet it’s always one step ahead of me. I want to write it down to exorcise it, so I can catch my breath again. I’ve been running for so long. I’m tired and weary. The boy next door is sitting in my lap. Yesterday he bit his lip open. The blister has filled with pus.

I remember a time when I’m awake and alive. I see myself. A bounding, freckled child. I run as fast as I can. The soles of my feet pound the asphalt. My heart is beating in my mouth. I run so I can feel how strong I am. My legs stick out of my short blue shorts. I am proud of the fact that a boy wore them before me. I feel brave in these shorts. The summer air caresses my legs. The gravel on the tarmac digs into my soles. My feet lift off from the ground. I am floating a hand’s breadth above the asphalt. I glide round the corner, down the small alleyway, to the stream. The water is brown and peaty, the riverbed is sand. I can see fish through the gaps between the planks on the wooden bridge. Dark streaks against a white background. I fly all the way to the woods. I spread my arms and swim through the air. I am happier than I’m allowed to be. I float over everything; over people, over the television in our living room. Then I plunge downwards. I’m falling. My scream wakes me.

Come back soon, we need to investigate, the doctors say. But there’s nothing to investigate. My body is strong. It’s something else that is oppressing me, choking me, almost stopping me from breathing.

I hold on to the story because nobody tells it. Silence is part of the family. It’s hard to describe — I can’t put my finger on it — because silence doesn’t consist of saying nothing. My parents and I talk about this and that, but the truth falls through the cracks, down deep. No sentence catches it. They say death is an end to life, but there is a life beyond death. People live on in the stories we tell each other. Even things we don’t talk about live on; they come back again in a different form.

This story is also a play. Appearing are: my parents, Judith and Hamid. My little sister, Elly, sits breathing down our tiny father’s neck. My mother holds me by the hand. The stage is lit by sunshine. Then Elly disappears. She exits into the dark backdrop. A gravestone thunders down onto the stage. We cry, we wail, we tear our hair out. Each one of us tumbles on our own, alone, into the blackness at the back of the stage. Finally Elly appears, transformed. She is much older, her eyes are dark. We stare at her. Then my mother puts her arms around her and embraces her. We surround the girl, cover her with our bodies. We are vampires. We shroud her. All that remains is a bare skeleton. A small child enters. It laughs and picks up a broom. It sweeps the stage clean. Then it throws the broom into the audience, crosses its legs and sits down, and says: So far, so good.

Queen

In the beginning is the pain. Sharp and spiky, it bores into my guts. It takes my breath away. I double over, whimper, groan. Then it’s over. The pain is gone. Suddenly I am free. I sit up again. I breathe in. I try to go back to sleep. But the cramps come back. The pain hollows me out. My moaning wakes my mother. She looks at me blearily. I’m lying on the sofa, in the dark. When the cramps come, I forget myself. You’re becoming a woman, my mother says. I can’t catch a breath now. The pain constricts my throat. My mother tries to hold me and rock me, but her hands are too clumsy. As if she were wearing boxing gloves. Help, I want to cry, please help me. What my mother would prefer to do is make her excuses and step away from this imposition, or keel over herself. Instead she frantically tips tablets onto the table, fumbles for her phone, asks for advice. The woman on the other end thinks we should come in. My mother says to me: Darling everything will be fine. Her boyfriend will drive us to the hospital. I give a loud groan. My mother quickly changes tack. She fetches the hot water bottle, makes tea. I feel the pain tugging at the skin on my face. My mother doesn’t wait for her boyfriend. She calls a taxi. The hospital admits us.

Appendix, the doctor in the emergency ward says, couldn’t be more obvious. My mother says: But my daughter had it out two years ago. The doctor scribbles on his notepad. He’s not receiving on this frequency. My mother chirps again: Can’t you see the scar? But the doctor’s pupils are reflected on the screen of his smartphone. My gaze roams around the room, looking for something to hang on to. An elephant on a poster. My eyes trace its folds, its tusks. The pain is sneaking up. From behind, like thunder behind clouds. My belly goes rigid, it is threatening to burst. A worm pushes its way through my guts. It threatens to blow me up. I can’t think any more, I can only feel. That’s what it will be like when you’re older and have children, the doctor in the emergency ward says. I’m only a child myself. At least in the eyes of the law. I haven’t played with dolls for a long time. The only thing I speak to my mother about is empty yoghurt pots and heaps of clothes. I whinge at her. Since she found this business informatics guy on the internet, she has lost her mind. I call him Hugo, although his name is Adam. He smiles and

ignores it. I have stopped hoping he will leave my mother. There’s nothing I hope for any more. If anything, I hope that I’ll grow breasts finally. That would be a step in the right direction. Those mounds give you power. I’m flat and angry. Sometimes I imagine waking up in the morning, transformed into a beetle. Ideas like that make me laugh. That makes time pass faster. I’m tired all the time. Only the pain wakes me. It returns with a vengeance. It rams into my belly.

The doctor hooks me up to the drip and puts me on the list for an operation. He wants to remove my appendix. My mother says again: Your colleague already took it out. The doctor prods my rigid belly. My mother stops fighting. She gives my name, our health insurance details. She called me Almut because of the north. Because of the stiff breeze on the island of Sylt, where she has never been; because of the tall blond boy that she never kissed, because she doesn’t like tall blonds; because of the seagulls, whose cries make her melancholy; and because of the seaweed and the salt which no longer cling to her legs: now it’s dark stretchy jeans with all their poisonous dyes instead. I’m also called Almut because it contains the German for courage, Mut, and my mother believed the name would give me some. I’m meant to grow big and strong. My mother looks at me and sees herself lying in the hospital bed. She strokes my hair. I shrink away from her hand. The doctor puts the cannula in my arm. The coldness of the anaesthetic runs into me. The lights over me glare. The anaesthetist counts backwards. Ten, nine, eight. I don’t even hear seven.

I’m still woozy from the anaesthetic when I see Ines for the first time. After that, nothing is ever the same again. My mouth is full of cotton wool, my eyelids are heavy. I’m a stone coming to life. Ines has the bed by the window. The backlight conjures a halo for her. Her features remain in shadow. On her bedside table on wheels are bottles with astronaut food inside them. Ines tells me that the yellow liquid tastes like banana, the red like strawberries. I’m envious. She eats as if she has already flown to the moon. I get boring invalid food. Only a tiny scar graces my belly. The loop in my bowel was untwisted just in time. Ines on the other hand went the whole hog: she got her appendix to burst. The poison flooded through her body. She seems to be an arm’s length ahead of me in everything. I’m thirteen, she is fourteen. Iiii-nes. The syllables suit her. First the expression of disgust, the devastating judgement. Then the sweet-talking ending, the salvation. Ines is neither particularly pretty nor ugly. Nothing about her is remarkable. Her brown hair is smooth, parted in the middle; her nightie is white like the sheets, starched. I dream about her. Water, waves, misadventure. Ines saves me from all of them. She pulls me out of the maelstrom by my hair. When I wake up, I tell her about it. Ines wrinkles her forehead. For the first time she encourages me to carry on talking. I tell her everything. My voice trembles. Ines says nothing. I feel naked. Ines is so certain, so strong. She doesn’t need words to make me understand. I can sense her superiority. She makes the roots of my hair stand up. She is a queen. I recognise that immediately. I don’t need anyone to tell me. I know a queen when I see one. A queen has nothing to lose. That’s why she gets everything. Suddenly I’m wide awake.

I’m happy to be in hospital, because I’m with Ines. Ines on the other hand misses her school. She paints me a picture of a place full of colour, light, music. The pupils there dance, paint, sing. They make pottery, build dens, bake bread, survey the land. Not every child is allowed to go to this school. Even Ines had to take a test. The headmistress gave her watercolours and a dampened sheet of paper. Ines dabbed the paintbrush over it. The colours ran into one another, mixed together. Ines gave her picture to the headmistress, who studied the colours. She scrutinised Ines, compared her with her painting. Those messy daubs were Ines’s ticket to paradise. This is how I imagine the school. The walls and roofs are steeply angled like the sides of a diamond. The garden is wild. Overgrown. Meadows, wildflowers, a field of wheat. A pond with waterlilies. A frog croaks. The midges dance above the reeds. A hedge shields the garden from the street. Sentries stand at the entrance gate. The two teachers shake every student’s hand. They check their body temperature and their eyes. Anyone who seems too cold has to run a lap of the building. Ines is always the right temperature. The nurses in the hospital are bewildered when they remove the thermometer from Ines’s body. They don’t know that Ines secretly chills it while the sisters rub me down with a washcloth. Ines doesn’t want to go home. She just wants to have everything under control. She wants to be the one who decides how she is doing. Despite her successful deception with the thermometer, Ines will have to stay in the clinic for a long time yet. But I’m meant to be leaving. After the weekend you’ll be back home, the nurses say. Aren’t you happy? I look at Ines. She is looking out of the window.

The walls in the hospital are coated with dirt-repellent paint. A colour like eggshells. Snot and tears roll off these walls. When no one is looking, I test it out. My mother brings me apples, a book. I ignore her. Since she left my father, I have been punishing her. I only ask my mother for one thing: I want to go to Ines’s school. My mother refuses. Laughing, she says she’s not one of those types. She doesn’t dream in pastels and she doesn’t believe in reincarnation. Anger wells up in me. I blow my mother out. Make her fade away. After a quarter of an hour of silence, she gives up. She says goodbye. Only her apples are left behind. One of them is gleaming red. It has a bruise. I weigh it in my hand. The apple smells juicy. I give it to Ines. She pierces it with a rusty needle. I fold my hands, bow my head. Ines anoints me with its juice. She says it heals all wounds. She says I’m something special, like a precious stone. That I just need to be polished. That what makes me special is encrusted, it only catches the light for a moment at a time. But that I’m in luck: Ines recognises me despite everything. She promises to help me. I don’t need my mother’s permission to go to her school, she says. I’m the only one that matters. She says I could pass the test. She prepares me. We train hard.

I need to learn everything from scratch again. Standing, walking, even the way I sit is wrong. Ines practises with me. I have to repeat everything a thousand times. At night she wakes me and asks me what music I like, how old I am, or what my favourite colour is. Quickly, I say: Waltzes, eleven and red. Ines tucks me up again and kisses me on the forehead. I don’t forget how old I actually am or that I much prefer green. But I’m a good pupil. I’m a quick learner. I know what my teacher wants to hear. Ines is pleased with my progress. I’m pleased that she is pleased. She changes my preferences, my hobbies, my experiences. I accept everything willingly. Ines says my name doesn’t suit me. My real name, my secret name, is Eleonore. She calls me Elly. I answer to it. Ines transforms me. She gives me new clothes and even a wig. I get changed in the bathroom. When I open the door, Ines stares at me. Shocked, I ask: Have I got everything right? I pluck at my hair hesitantly. Ines doesn’t say anything. Stiff as a marionette, she reaches a hand out to me. She pulls me onto her knees. I’m too big for that, but it doesn’t bother her. She holds me in her arms, rocks me, and hums. I keep completely still. The wig is black and woolly. My own hair is blonde and thin. Ines doesn’t care that the wig looks fake. She strokes my pretend hair. A cleaner catches us. She laughs at the sight. I feel helpless, angry. Ines is shaking. She is in danger of losing her composure, I can see it. But she pulls herself together. The next minute she is my queen again. Powerful, untouchable. The cleaner says we should go outside, get some fresh air, not just lock ourselves away in the room. We fling ourselves onto our beds. She swishes the mop around us. We let her talk. The grown-ups believe it’s all just a game.

The doctor calls the children from the room next door to my bedside. They are allowed to watch. The plastic thread on my scar is about to be taken out. The doctor pulls my pyjama trousers down below my belly button. I’m afraid they will slip further. I try not to breathe. The doctor plucks at the red bulge on my skin with tweezers. Finally he catches the blue thread. A boy is staring at my stomach. He pulls a face, he’s disgusted. I hate him. Ines

walks out. Immediately the room seems darker. The doctor holds the blue thread up in the air. We’ll soon be shot of you, he jokes. He praises me: The wound is healing in textbook fashion. When he has gone, Ines passes me her rusty needle. I dip it in the toilet. Then I pick my scar apart with it. Ines helps me. We spread the sheet over the blood. The cloth soaks it up. The fever comes almost at once. The nurses can’t explain it. They give me juice. I spit it out when they aren’t looking.

At night, when all the sick children are asleep, Ines dances for me. She loosens the curtain from its hooks, wraps it around her body like a veil. It’s dark in the room. The only light is from the moon. The darkness is velvety. It envelops us. A tawny owl calls. A night nurse is patrolling the corridor. She walks past our door at regular intervals. She never comes into the room. I’m convinced Ines stops her. Ines doesn’t need to issue orders. She can control thoughts. I believe it. I’m not allowed to talk while Ines is dancing. Even a cough will break the spell. Ines dances without music. Her face is motionless; she gazes off into infinity. She seems to get her instructions from there. Only her body is here with me. Ines’s movements are carefully described. She doesn’t hop, she doesn’t sway. It is a sublime dance, a confident dance. Her arms swing, they reach far into space. Her hands stretch up into the air, almost as high as the stars in the sky. Then her body collapses in on itself. She crouches down for a second, pirouettes, rises up again. Her movements tell me what I can’t understand. She is letting me in on a secret. Ines is beautiful when she dances. I want to touch her, but I don’t dare.

My pyjamas stick to my body. I am enjoying the fever, my weakness, the inner turmoil. Ines is my ally. We live in a twilight realm. Our sick room belongs to us and us only. It is a capsule. We are floating through space. Ines already has her astronaut food, and I am weightless. I don’t know which way is up or down any more, or who I really am. I am merging into Elly. As soon as the other children are asleep, the ward belongs to us. Ines and I haunt the place. We borrow shoes and lipstick from the nurses’ room. We play tag under the X-ray machine. Sometimes at night we even steal out onto the lawn. We lie down in the grass. We shiver together. We make ourselves ill. No one is allowed to cure us. We hold hands. Ines says I’m nearly there. That I’ll soon understand. That I’ll reach enlightenment. As she says it, I can already sense the peace that she is promising me. As soon as we’re alone, I turn into Elly, and Ines spoils me. She feeds me forbidden sweets, she teaches me new songs. We chase each other. If I manage to catch Ines, I’m allowed to hug her. I’m happy as Elly. I feel free. As Elly, I’m allowed to be daft. I can joke with Ines, tease her. As Elly, I have power. I’m close to Ines. I am her creation. It’s not about going to her school any more. I just want to be with Ines.

Elly

Elly